Hebrew Letters & Movements

Letter Forms

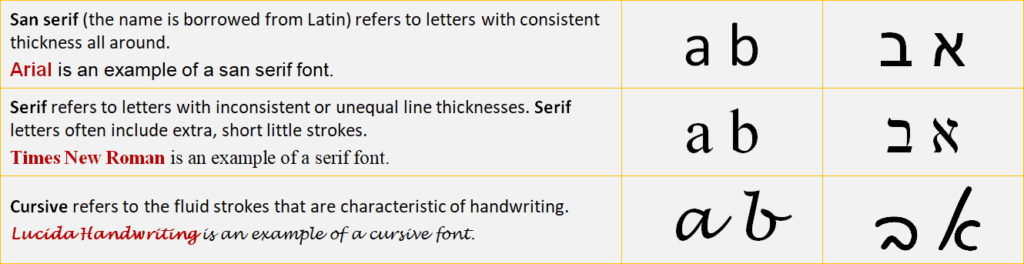

Hebrew letters can appear in various forms and styles. Common forms include:

- San serif block letters – easy to read

- Serif block letters – traditional, commonly used for scripture, best for writing with your quill

- Cursive – easy and quickest to write with a pen or pencil

אבגד (Abgad)

The Hebrew reading/writing system is an abgad. An abgad is a writing system whose letters represent consonantal sounds (a consonantal alphabet). With an abgad, the reader is often left to infer the vowels.

Hebrew Letters

Movements (Vowels)

In Hebrew, vowels are considered an optional, secondary feature. The language assumes readers already possess sufficient knowledge to figure things out. Hebrew affords writers the discretion to indicate vowels in three primary ways. A writer may:

- Use no notation whatsoever, trusting the reader to deduce the missing vowels.

- Insert flexible letters to stand in for some—not all—vowels.

- Add נִקּוּד (NI.KUD) markings to explicitly indicate each vowel.

נִיקּוּד (Nikud)

A Long, Long Note about the שווא Schwa

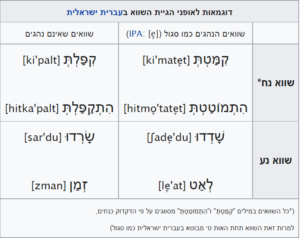

For a thing that should really be simple, the original Hebrew schwa is anything but. I normally exclude this segment from beginners’ level learning. Because many of you have asked about it, I’ve added an explanation of the schwa, and how it interacts with vowels and the two dagesh types. The following snippet from Wikipedia shows 4 forms of the schwa. What?:

- 2 unvoiced (“resting”)

- 2 voiced (“moving”)

A voiced schwa sounds like an E vowel, while an unvoiced schwa is, well, a schwa! So, how do you know when to use which? Here are my top two answers:

Most people will just memorize words correctly. The more you know, the better you intuit.

If you really want to know the nuts and bolts of the schwa, get yourself a refreshing beverage. This could take a while… We’ve listed some common rules for schwa usage. This is not, by any means, an exhaustive list.

| Example | If we have… | Then… (and a mnemonic, if applicable) |

| מְּאֹד מְדַבְּרִים | A schwa on a word’s first letter | This schwa is always voiced/moving. (In Hebrew, we refer to a voiced schwa as a “moving schwa.”) First thing in the morning, this schwa awakens energized and is therefore voiced/moving. |

| אִשְׁתְּךָ יִלְבְּשׁוּ | Schwas on two consecutive letters in the middle of a word | The first schwa is always silent/at-rest, while the next schwa is voiced/moving, but only so long as this second schwa is not joined to the word’s final consonant. In friend pairs, one’s typically louder (voiced/moving) than the other (silent/at-rest). Of course, there are exceptions. Sometimes both friends are silent/at-rest . |

| יָשַׁבְתְּ הִתְקַפַּלְתְּ | Schwas on two consecutive letters at the end of a word | Both of these schwas are always silent/at-rest. |

| הַלְלוּ | A schwa on the first of two identical, consecutive letters | This schwa is always voiced/moving. |

| מֶרְכָּבָה | A schwa on a letter that precedes a lightly emphasized בגדכפת letter (i.e., with a dagesh kal) | This schwa is always silent/at-rest. |

| מִקְדַּשׁ | A schwa on a letter that precedes a heavily emphasized letter (i.e., with the rarely articulated dagesh khazak, which will never be אהחער, but might coincide with בגדכפת) | Unpredictable; a rule of thumb: This schwa is generally silent/at-rest at the beginning of a syllable. |

| וּשְׁנֵי | If you’re going for a masoretic or ancient Hebrew pronunciation, much of what you read above does not apply | More often than not, this schwa is voiced/moving. |

Additional information is presented in this Hebrew-language video on the topic.

Flexible Letters

The following five (out of Hebrew’s 22) letters are flexible, meaning that they can function as consonants or as vowels: